- Background

- ScaFi User Manual

- ScaFi Developer Manual

- Something missing?

Background

Introduction: Aggregate Programming

Aggregate Programming is a paradigm for the development of collective adaptive systems (CAS). It provides a compositional, functional programming model for expressing the self-organising behaviour of a CAS from a global perspective. Aggregate Computing (AC) is formally grounded in the field calculus (FC), a minimal core language that captures the key mechanisms for bridging local and global behaviour. FC is based on the notion of a (computational) field, a (possibly dynamic) map from a (possibly dynamic) domain of devices to computational values.

Aggregate Computing is based on a logical model that can be mapped diversely onto physical infrastructure.

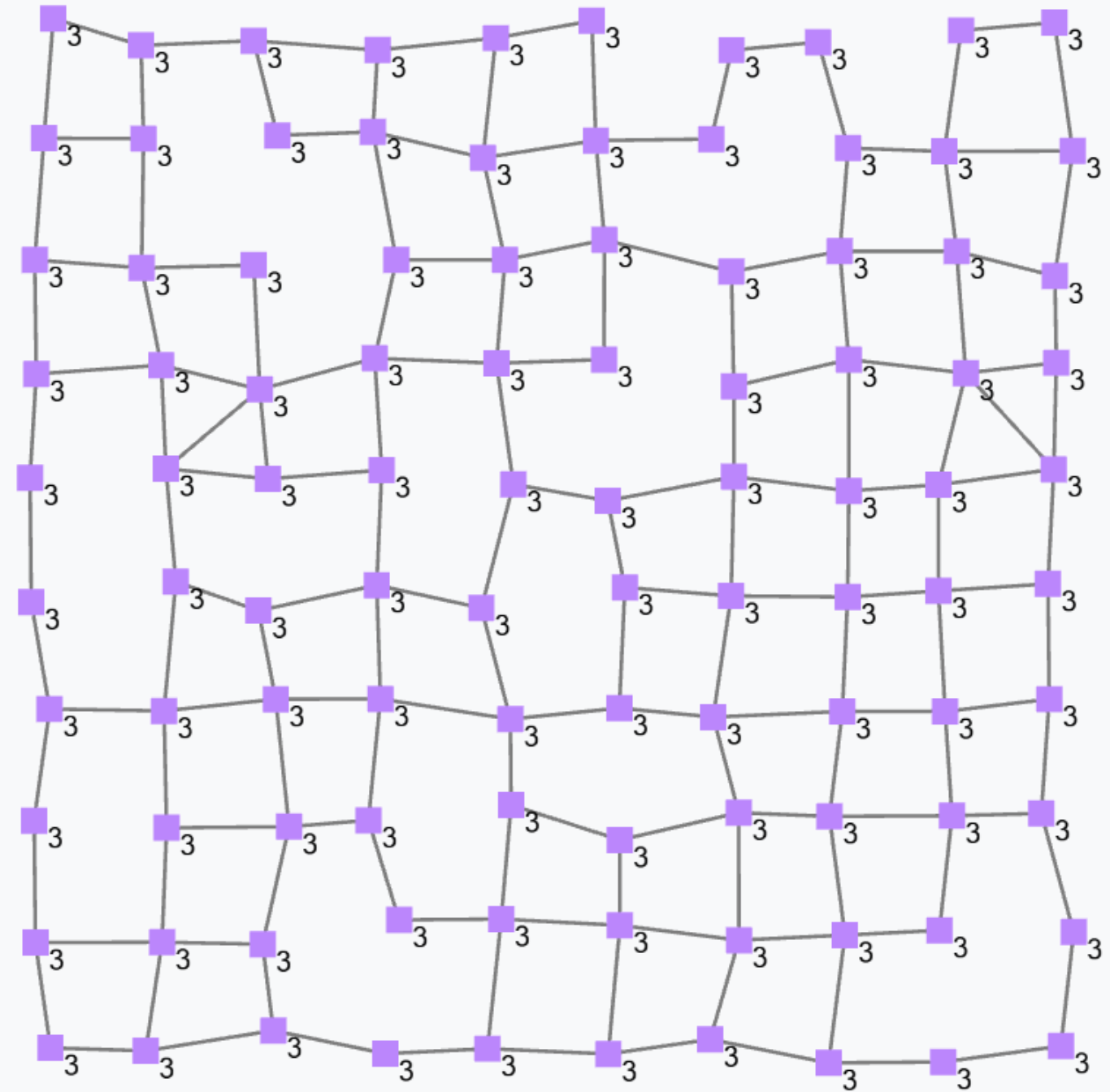

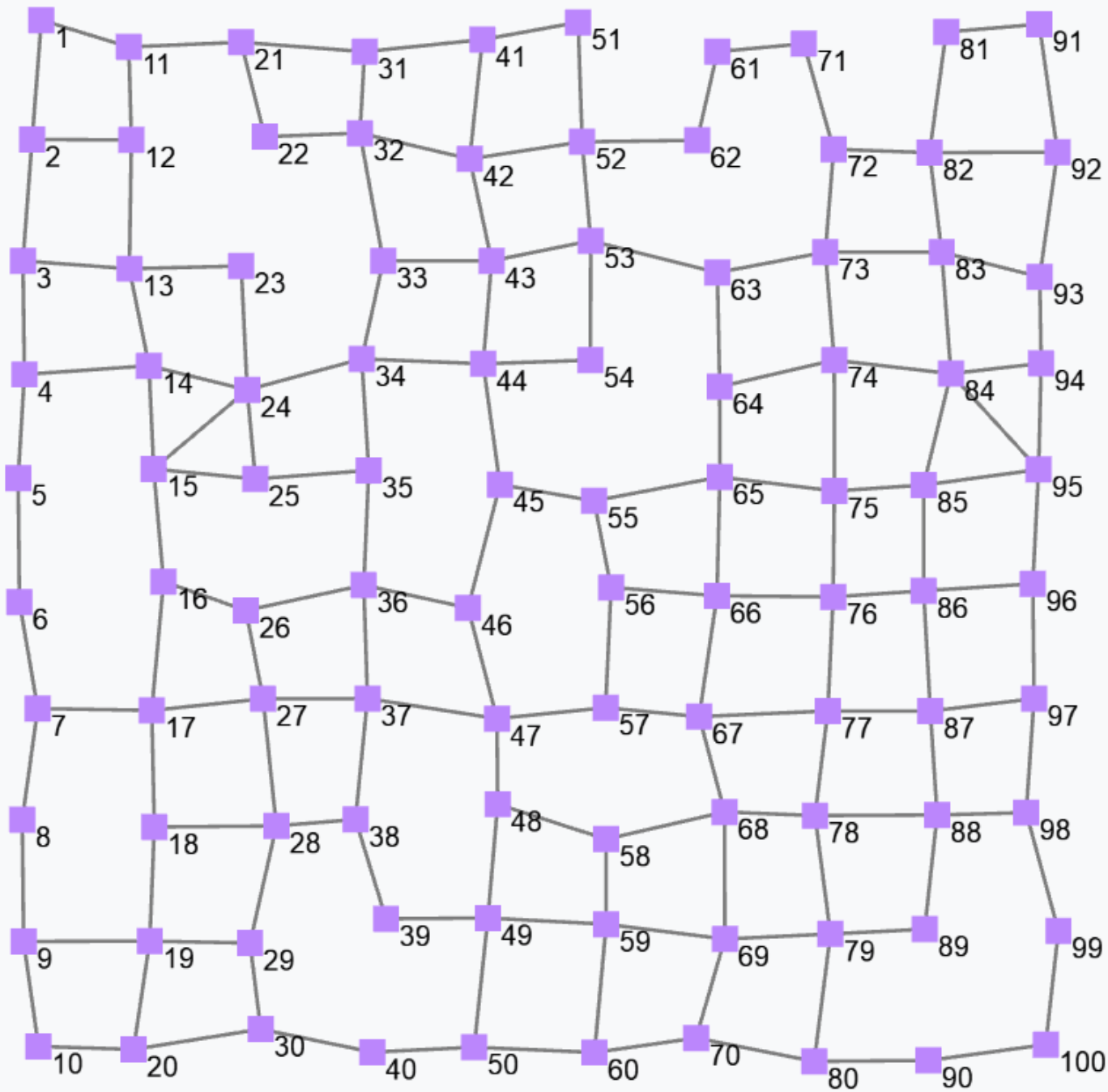

- From a structural point of view, an aggregate system is merely a graph or network of devices (also called: nodes, agents, robots). The edges connecting nodes represent logical communication channels that are set up by the aggregate computing platform according to an application-specific neighbouring relationship (which, for situated systems, is typically a communication range).

- From a behavioural point of view, any device “continuously” interprets the aggregate program against its local context.

- From an interactional point of view, any device continuously interacts with its neighbours to acquire and propagate context. This is what enables local activity to influence global activity and vice versa.

Execution model

In practice, devices sustain the aggregate computation through asynchronous sense-compute-(inter)act rounds which conceptually consist of the following steps:

- Context update: the device retrieves previous state, environment data (through sensors), and messages from neighbours.

- Aggregate program execution: the field computation is executed against the local context; this yields an output.

- Action

- Export broadcasting to neighbours: from the output, a subset of data (called an export) for neighbour coordination can be automatically derived; the export has to be broadcast to the entire neighbourhood.

- Execution of actuators: the output of the program can describe a set of actuations to be performed on the environment.

A code example of round execution in ScaFi is shown in Building Aggregate Systems.

Programming model

Aggregate computing is a macro-programming paradigm where a single program (called the aggregate program) defines the overall behaviour of a network of devices or agents.

The aggregate program does not explicitly refer to the execution model discussed in the previous section, i.e., it somewhat abstracts from it (though in some cases it may assume that the execution model has certain characteristics). Instead, it expresses how input fields maps to output fields: for instance, how a field of temperature sensor readings maps to a field of warnings; or, as another example, how a field of service requests and resource advertisements map to a field of task allocations.

A paradigmatic example is the Self-Organising Coordination Regions pattern, where a situated system is split into leader-regulated areas, where each leader collects data from devices in its area and orchestrates the activity in its area. An aggregate program to realise this pattern could be as follows in ScaFi:

val leader: Boolean = S(meanDistanceBetweenLeaders) // distributed leader election

val distanceToLeader: Double = distanceTo(leader)

val followedLeader: ID = G(distanceToLeader, mid(), x => x)

val data: Map[ID,Data] = C[Double,Map[ID,Data]](distanceToLeader, _++_, Map(mid() -> getData()), Map.empty)

// now the leader can use `data` to take decisions and instruct its followersNotice that each value is conceptually a field (i.e., fields are a global denotation of program inputs, outputs, and intermediate results).

For instance, the Boolean value leader will be true or false locally at each device according to whether that device is a leader or not;

globally, leader can also be interpreted as a Boolean field denoting leaders. The same goes for the other values as well: distanceToLeader is the field of minimum distances from leaders; followedLeader is the field mapping each device to the leader it currently follows;

data is a field of maps mapping devices to corresponding data items (here, we abstract from type Data).

ScaFi User Manual

Hello, ScaFi

- Consider the following repository: https://github.com/scafi/hello-scafi

As another example, consider the following steps.

Step 1: Add the dependency to scafi in your project (e.g., via sbt)

Step 1-A: SBT

val scafi_core = "it.unibo.scafi" %% "scafi-core" % "1.1.5"

val scafi_simulator_gui = "it.unibo.scafi" %% "scafi-simulator-gui" % "1.1.5"

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(scafi_core, scafi_simulator_gui)Step 1-B: GRADLE (build.gradle.kts)

plugins {

java

scala

}

dependencies {

implementation("org.scala-lang:scala-library:2.13.2")

implementation("it.unibo.scafi:scafi-core_2.13:1.1.5")

implementation("it.unibo.scafi:scafi-simulator-gui_2.13:1.1.5")

// Note: before ScaFi 0.3.3, the group ID was 'it.unibo.apice.scafiteam'

}

// the following may be needed when running using Java 11

tasks.withType<ScalaCompile> {

sourceCompatibility = "1.8"

targetCompatibility = "1.8"

}Step 2: Use the API (e.g., to set up a simple simulation)

Step 2-1: Import or define an incarnation (a family of types),

from which you can import types like AggregateProgram

package experiments

// Method #1: Use an incarnation which is already defined

import it.unibo.scafi.incarnations.BasicSimulationIncarnation.AggregateProgram

// Method #2: Define a custom incarnation and import stuff from it

object MyIncarnation extends it.unibo.scafi.incarnations.BasicAbstractIncarnation

import MyIncarnation._Step 2-2: Define an AggregateProgram which expresses the global behaviour of an ensemble.

// An "aggregate program" can be seen as a function from a Context to an Export

// The Context is the input for a local computation: including state

// from previous computations, sensor data, and exports from neighbours.

// The export is a tree-like data structure that contains all the information needed

// for coordinating with neighbours. It also contains the output of the computation.

class MyAggregateProgram extends AggregateProgram with StandardSensorNames {

// Main program expression driving the ensemble

// This is run in a loop for each agent

// According to this expression, coordination messages are automatically generated

// The platform/middleware/simulator is responsible for coordination

override def main() = gradient(isSource)

// The gradient is the (self-adaptive) field of the minimum distances from source nodes

// `rep` is the construct for state transformation (remember the round-by-round loop behaviour)

// `mux` is a purely functional multiplexer (selects the first or second branch according to condition)

// `foldhoodPlus` folds over the neighbourhood (think like Scala's fold)

// (`Plus` means "without self"--with plain `foldhood`, the device itself is folded)

// `nbr(e)` denotes the values to be locally computed and shared with neighbours

// `nbrRange` is a sensor that, when folding, returns the distance wrt each neighbour

def gradient(source: Boolean): Double =

rep(Double.PositiveInfinity){ distance =>

mux(source) { 0.0 } {

foldhoodPlus(Double.PositiveInfinity)(Math.min)(nbr{distance}+nbrRange)

}

}

// A custom local sensor

def isSource = sense[Boolean]("sens1")

// A custom "neighbouring sensor"

def nbrRange = nbrvar[Double](NBR_RANGE)

}Step 2-3: Use the ScaFi internal simulator to run the program on a predefined network of devices.

import it.unibo.scafi.simulation.frontend.{Launcher, Settings}

object SimulationRunner extends Launcher {

Settings.Sim_ProgramClass = "experiments.MyAggregateProgram"

Settings.ShowConfigPanel = true

launch()

}Alternatively, you can use the approach taken in Building Aggregate Systems.

Indeed, an AggregateSystem object can be seen as a function from Context to Export:

you give a certain context, and get some export. The export must be passed to neighbours so that they can build their own context

and re-interpret the aggregate program.

Step 2-4: After a simple investigation, you may want to switch to a more sophisticated simulator, like Alchemist. Take a look at Alchemist simulator for details about the use of ScaFi within Alchemist.

ScaFi Architecture

From a deployment perspective, ScaFi consists of the following modules:

scafi-commons: provides basic entities (e.g., spatial and temporal abstractions)scafi-core: represents the core of the project and provides an implementation of the ScaFi aggregate programming DSL, together with its standard libraryscafi-simulator: provides basic support for simulating aggregate systemsscafi-simulator-GUI: provides a GUI for visualising simulations of aggregate systemsspala: provides an actor-based aggregate computing middlewarescafi-distributed: ScaFi integration-layer forspala

The whole structure is resumed in the following picture:

The modules to be imported (e.g., via sbt or Gradle) depend on the use case:

- Development of a real-world aggregate application.

Bring

scafi-corein for a fine-grained integration. For a more straightforward distributed system setup, take a look atscafi-distributed. - Play, exercise, and experiment with aggregate programming.

Bring

scafi-corein for writing aggregate programs as well asscafi-simulator-guito quickly render an executing system. - Set up sophisticated simulations

Bring

scafi-corein for writing aggregate programs and either (A) leverage the basic machinery provided byscafi-simulator, or (B) leverage the ScaFi support provided by Alchemist.

Aggregate Programming: Step-by-Step

Here, we explain the basic constructs of the field calculus, which are the core of the aggregate programming paradigm. By combining these constructs, higher-level functions can be defined to capture increasingly complex collective behaviour.

Consider the Constructs trait.

trait Constructs {

def rep[A](init: => A)(fun: A => A): A

def nbr[A](expr: => A): A

def foldhood[A](init: => A)(acc: (A, A) => A)(expr: => A): A

def aggregate[A](f: => A): A

// the following (aggregate IF construct) can be defined upon AGGREGATE()

def branch[A](cond: => Boolean)(th: => A)(el: => A)

// the following is a variant of REP()

def share[A](init: => A)(fun: (A, () => A) => A): A

def mid: ID

def sense[A](sensorName: String): A

def nbrvar[A](name: CNAME): A

}This trait is implemented by AggregateProgram (the class to extend for defining new aggregate programs). In summary:

rep(init)(f)captures state evolution, starting from aninitvalue that is updated each round throughfun;nbr(e)captures communication, of the value computed from itseexpression, with neighbours; it is used only inside the argumentexproffoldhood(init)(acc)(expr), which supports neighbourhood data aggregation, through a standard “fold” of functional programming with initial valueinit, accumulator functionacc, and the set of values to fold over obtained by evaluatingexpragainst all neighbours;branch(cond)(th)(el), which can also be called asbranch(cond){ th } { el }captures domain partitioning (space-time branching): essentially, the devices for whichcondevaluates totruewill run sub-computationth, while the others will runel;midis a built-in sensor providing the identifier of devices;sense(sensorName)abstracts access to local sensors; andnbrvar(sensorName)abstracts access to “neighbouring sensors” that behave similarly tonbrbut are provided by the platform: i.e., such sensors provide a value for each neighbour.

Now let’s consider a progression of examples to help you get acquainted with the programming model and the aforementioned constructs. Notice that these examples can be run on ScaFi Web.

Basic expressions

In ScaFi a usual expression such as, for instance,

1+2is to be seen as a constant uniform field (since it does not change over time and does not change across space) holding local value 3 at any point of the space-time domain. More specifically, this denotes a global expression where a field of 1s and a field of 2s are summed together through the field operator +, which works like a point-wise application of its local counterpart.

Running the above program by an aggregate system will produce the following result, where the output of the program is shown as a value for each node.

A constant field does not need to be uniform. For instance, given a static network of devices, then

mid()denotes the field of device identifiers, which we may assume it does not change across time but does vary in space: so, it would be a constant non-uniform field.

Dynamically evolving fields

Non-constant fields can be generated by querying sensors in non-stationary environments

and can also be programmatically defined by the rep operator; for instance, expression

rep(0)(x => x+1)counts how many rounds each device has executed. Indeed, the first time the rep expression is evaluated at some device, x is bound to 0, and the expression evaluates to 0+1=1; the next round on the same device, x is bound to 1 (i.e., to the value of the expression in the previous round) and the expression evaluates to 1+1=2; and so on. It is still – in general – a non-uniform field since the update phase and frequency of the devices may vary both between devices and across time for a given device. The following figure shows a snapshot of a field generated by the above expression.

Notice that if we assume a bulk synchronous execution model, the output of the above expression would be a non-constant but uniform field.

Neighbourhood data aggregation

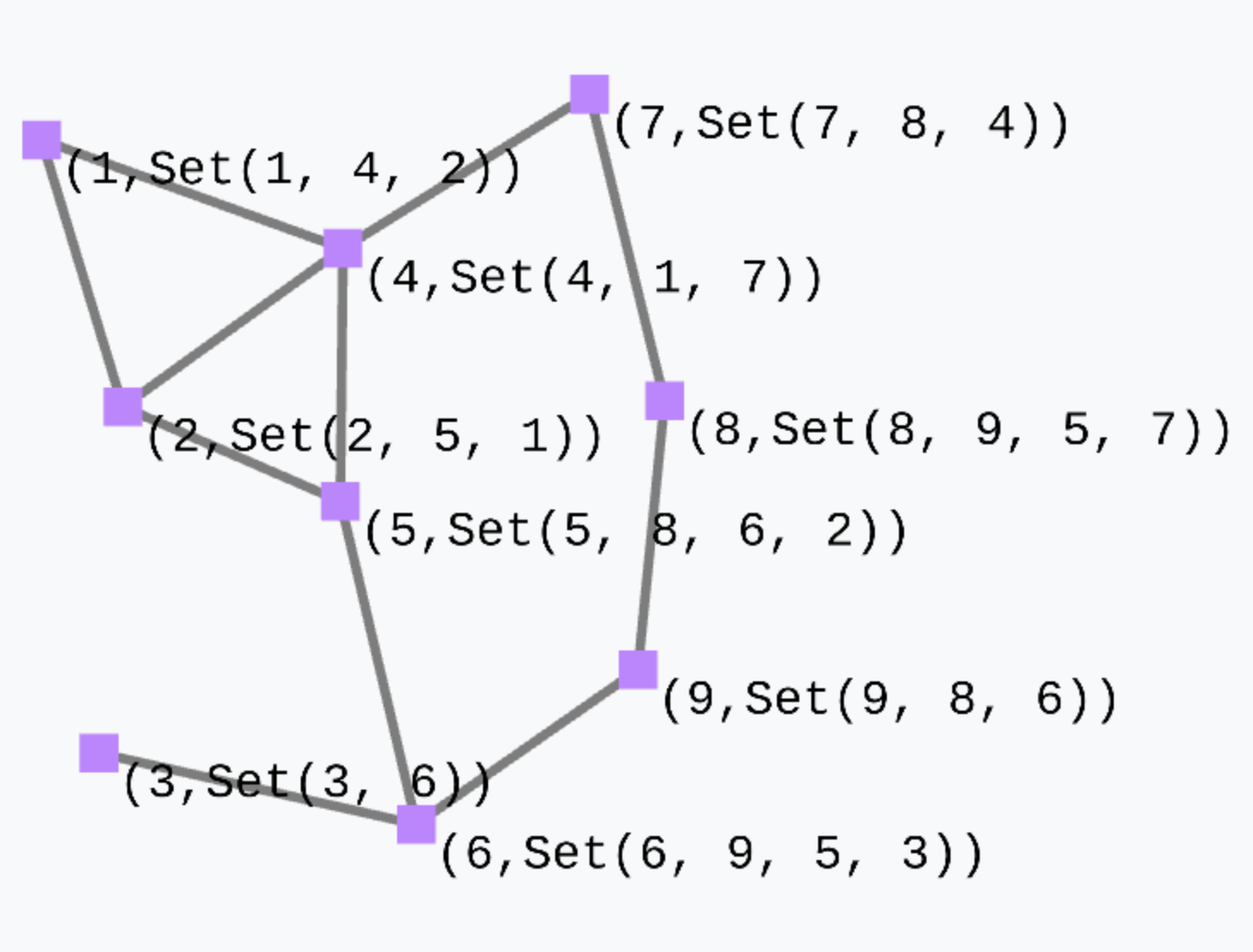

Consider the simple expression

(mid(), foldhood[Set[ID]](Set())(_++_)(Set(nbr(mid()))))which outputs a tuple where the first element is the device ID and the second element is a set obtained by collecting, in each node, the set of IDs of its neighbours.

There is a variant of foldhood which is called foldhoodPlus which does not consider the device itself when folding over the neighbourhood.

Local to global: the case of the gradient field

Collective intelligence can be programmed by letting the local affect the global and vice versa. This operation is supported by combining rep with foldhood and nbr.

To illustrate this combination of operators, we provide the paradigmatic example of the gradient field, which is the field of minimum distances from any node to its closest “source node”.

rep(Double.PositiveInfinity)(distance =>

mux(sense[Boolean]("sensor")){

0.0

}{

minHoodPlus(nbr{distance} + nbrRange)

}

)Specifically:

- The gradient value at each node is dynamically evolved using

rep. This is necessary to allow a node to share its previous gradient value with neighbours. The default value isDouble.PositiveInfinitysince by default a node is at an infinite distance from asource(since it may not be reachable in general). - The

mux(c)(th)(el)evaluates its expressionthandeland then uses the Boolean conditioncto select either the former (whencistrue) or the latter (whencisfalse). - If a node is a source (i.e., if sensing the Boolean sensor

sensorreturnstrue), then its gradient value is0(by definition). - If a node is not a source, then will take as its gradient value the output of expression

minHoodPlus(nbr{distance} + nbrRange). minHoodPlus(e)is the same asfoldhoodPlus(Double.NegativeInfinity)(Math.min)(e), namely, it selects the minimum value among those obtained by evaluatingeagainst the neighbours (excluded the device itself).- The argument of

mingHoodPlusisnbr{distance} + nbrRange(), which basically amounts to calculating, for each neighbour, the sum of the neighbour’s most recent gradient value and the corresponding distance to that neighbour (obtained by neighbouring sensornbrRange, which may be thought asnbrvar[Double]("nbrRange")).

The output of this gradient (once stabilised after some rounds) is as follows.

Such a gradient algorithm is self-healing: perturbing the network (e.g. moving nodes, changing sources) will make the gradient adjust to eventually converge to the “correct” field.

Simulating Aggregate Systems

Simulation of aggregate systems involves the following:

- Defining the structure of an aggregate system: in terms of devices (including their sensors and actuators), connectivity between devices (neighbouring relationship), and the environment in which devices are situated.

- Defining the behaviour of an aggregate system: through an aggregate program expressed in the ScaFi DSL.

- Defining the simulation setup: including simulation parameters, data to be exported, environment dynamics, and scheduling of computation rounds.

ScaFi simulator

The ScaFi simulator consists of multiple modules:

scafi-simulator: provides a basic support for simulating aggregate systemsscafi-simulator-gui: provides a Swing GUI for visualising simulations of aggregate systemsscafi-simulator-gui-new: provides a JavaFX GUI for visualising simulations of aggregate systems- NOTE: there is also on-going work for adding support to 3D simulations, see PR#38

ScaFi simulator engine

The ScaFi simulator engine is quite basic.

The idea for its usage is to leverage a factory, object simulatorFactory,

to build a simulation NETWORK object,

upon which various

exec methods are available for scheduling computation rounds on the devices.

On a network, there are also methods like addSensor and chgSensorValue

for programming the sensors of devices.

Consider the following example:

object DemoSequenceLauncher extends App {

val net = simulatorFactory.gridLike(GridSettings(6, 4, stepx = 1, stepy = 1), rng = 1.1)

net.addSensor(name = "sensor", value = 0)

net.chgSensorValue(name = "sensor", ids = Set(1), value = 1)

net.addSensor(name = "source", value = false)

net.chgSensorValue(name = "source", ids = Set(3), value = true)

net.addSensor(name = "sensor2", value = 0)

net.chgSensorValue(name = "sensor2", ids = Set(98), value = 1)

net.addSensor(name = "obstacle", value = false)

net.chgSensorValue(name = "obstacle", ids = Set(44,45,46,54,55,56,64,65,66), value = true)

net.addSensor(name = "label", value = "no")

net.chgSensorValue(name = "label", ids = Set(1), value = "go")

var v = java.lang.System.currentTimeMillis()

net.executeMany(

node = DemoSequence,//new HopGradient("source"),

size = 1000000,

action = (n,i) => {

if (i % 1000 == 0) {

println(net)

val newv = java.lang.System.currentTimeMillis()

println(newv-v)

println(net.context(4))

v=newv

}

})

}

Graphical simulator

For the usage of the graphical simulator, consider the following example:

package experiments

import it.unibo.scafi.incarnations.BasicSimulationIncarnation.AggregateProgram

object MyAggregateProgram extends AggregateProgram with StandardSensorNames {

override def main() = gradient(isSource)

def gradient(source: Boolean): Double =

rep(Double.PositiveInfinity){ distance =>

mux(source) { 0.0 } {

foldhood(Double.PositiveInfinity)(Math.min)(nbr{distance} + nbrRange)

}

}

def isSource = sense[Boolean]("source")

def nbrRange = nbrvar[Double](NBR_RANGE)

}

import it.unibo.scafi.simulation.gui.{Launcher, Settings}

object SimulationRunner extends Launcher {

Settings.Sim_ProgramClass = "experiments.MyAggregateProgram"

Settings.ShowConfigPanel = true

launch()

}By running the SimulationRunner program, the simulator will show up.

Setting Settings.ShowConfigPanel can be used to configure whether a launcher window has to be shown or not.

In the latter case, the simulation will immediately start by running program Settings.Sim_ProgramClass

through a default simulation model (random network with random sequential scheduling and instantaneous, perfect communication with neighbours at the end of each round).

Alchemist simulator

- Consider the following skeleton repository: https://github.com/scafi/learning-scafi-alchemist

- Take a look at this tutorial for ScaFi-Alchemist by G. Audrito

The ScaFi specific part in an Alchemist simulation descriptor is as follows:

incarnation: scafi

pools:

- pool: &program

- time-distribution: 1

type: Event

actions:

- type: RunScafiProgram

parameters: [it.unibo.casestudy.MyProgram, 5.0]

# 1st argument is the fully-qualified classname of your program (class extending AggregateProgram)

# 2nd argument is retention time (i.e., amount of simulated time for which exports by neighbours are kept)

- program: send # this is needed for broadcasting export to neighbours after program execution

NOTE: the send program is needed, otherwise there would be no communication among devices,

preventing the unfolding of the aggregate logic.

NOTE: the ScaFi incarnation does not attempt to create defaults for undeclared molecules.

So, you need to declare all your molecules (including exports–otherwise, the exporter component will try to export a yet-to-be-created molecule) before accessing them (e.g., be sure to perform a node.put() before a corresponding node.get()), or the following error might occur The molecule does not exist and cannot create empty concentration.

A full Alchemist simulation descriptor is as follows (node: refer to the Alchemist Documentation for more up-to-date information):

variables:

random: &random

min: 0

max: 29

step: 1

default: 2

export:

- time

seeds:

scenario: *random

simulation: *random

incarnation: scafi

environment:

type: Continuous2DEnvironment

parameters: []

network-model:

type: ConnectWithinDistance #*connectionType

parameters: [*range]

pools:

- pool: &program

- time-distribution:

type: ExponentialTime

parameters: [1]

type: Event

actions:

- type: RunScafiProgram

parameters: [it.unibo.casestudy.MyProgram, 5.0]

- program: send

- pool: &move

- time-distribution: 1

type: Event

actions: []

displacements:

- in:

type: Grid

parameters: [0, 0, 200, 80, 10, 10, 1, 1]

programs:

- *move

- *program

contents:

- molecule: test

concentration: true

Building Aggregate Systems

The major challenge in building aggregate systems is dealing with distribution.

Executing individual computational rounds is very easy, as demonstrated by the following snippet (standalone setup):

import it.unibo.scafi.incarnations.BasicAbstractIncarnation

object MyIncarnation extends BasicAbstractIncarnation

import MyIncarnation._

class BasicUsageProgram extends AggregateProgram {

override def main(): Any = rep(0)(_ + 1)

}

object BasicUsage extends App {

val program = new BasicUsageProgram()

val c1 = factory.context(selfId = 0, exports = Map(), lsens = Map(), nbsens = Map())

val e1 = program.round(c1)

val c2 = factory.context(0, Map(0 -> e1))

val e2 = program.round(c2)

println(s"c1=$c1\ne1=$e1\n\nc2=$c2\ne2=$e2")

}The following activites must be implemented

- execution of a reactive or temporally-delayed loop for executing computation rounds

- discovery of neighbours, and corresponding send and reception of exports from neighbours

- de/serialisation of exports (definition of the format, and transparent de/serialisation)

- implementation of a logical neighbouring relationship

- using a time window for retention of exports which also takes into account failure in export delivery

- implementation of an interface to sensors and actuators

Many of such activities are application- and deployment-specific, so it is not easy to come up with a general middleware solution. However, we are working on it.

Take a look at the following paper for middleware- and deployment-level considerations:

ScaFi Standard Library: an Overview

The ScaFi standard library is organised into a number of modules such as:

FieldUtils: define functionality to simplify aggregation of values from neighbours, accessible through two objectsincludingSelforexcludingSelfwith obvious semantics:sumHood(e),unionHood(e),unionHoodSet(e),mergeHood(e)(overwritePolicy),anyHood(e),everyHood(e)Gradients: defines gradient functions, such as:classicGradient(src,metric)BlockG: defines the gradient-cast (G) building block for propagating information, and related functionality such as:distanceTo(src,metric),broadcast(src,x,metric),channel(src,target,width),BlockC: defines the converge-cast (C) building block for collecting information along a spanning tree

BlockS: defines the sparse-choice (S) building block for leader electionBlocksWithGC: defines functionality that leverageCandG, such as:summarize(sink,acc,local,Null),average(sink,x)StateManagement: provides utility functions overrep, such as:roundCounter(),remember(x),delay(x),captureChange(x,initially),countChanges(x,initially),goesUp(x),goesDown(x)TimeUtils: provides time-related functionality, such as:T(init,floor,decay)and variants,timer(length),limitedMemory(x,y,timeout),clock(len,decay),sharedTimeWithDecay(period,dt),cyclicTimerWithDacay(len,decay)CustomSpawn: provides support for aggregate processes throughspawnfunction

To use a library component, just mix in your aggregate program class using the keyword with:

class MyProgram extends AggregateProgram with BlockG with BlockS { /*...*/ }

Leader election (S)

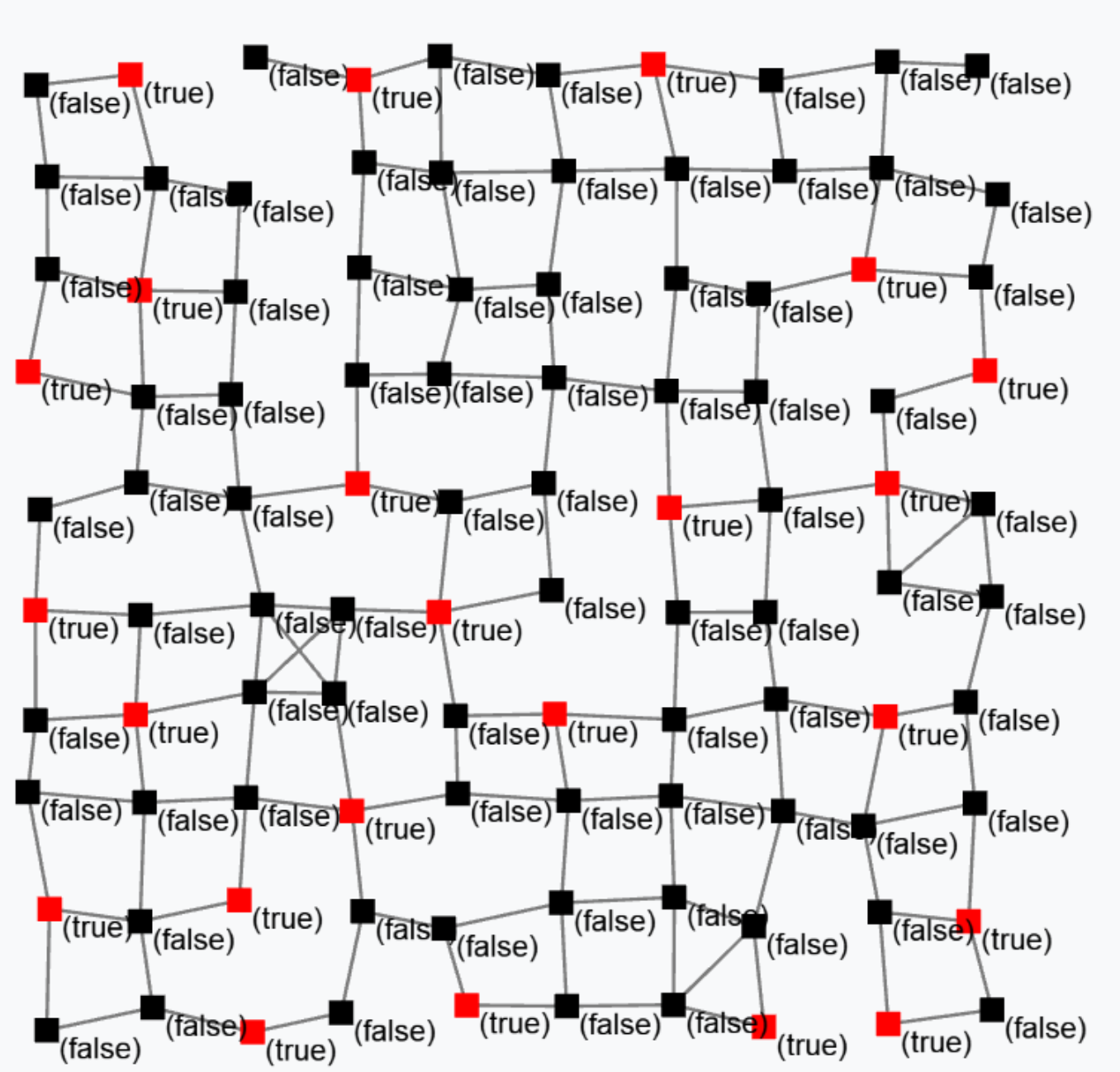

Block S (Sparse-choice) is used to perform a decentralised leader election on a spatial basis.

S(grain = 100, metric = nbrRange)

The previous snippet is used to elect leaders with a mean distance of 100 metres between two leaders. The output is a Boolean field that is true in correspondence of devices that are currently leaders. Leaders are shown in red in the following figure.

More building blocks

Please consult the ScaFi API (ScalaDoc) for more aggregate programming building blocks.

ScaFi Developer Manual

For project contributors

Contributions to this project are welcome. Some advices:

- As we use git flow, use

feature-xxxbranches. - We recommend forking the project, developing your stuff, then contributing back via pull requests (PRs) directly from the Web interface.

- Stay in sync with the

developbranch: pull often fromdevelop, so that you don’t diverge too much from the main development line. - Avoid introducing technical debt. In any case, merge requests will be reviewed before merge.

Contributing process

Follow these steps to contribute.

- Fork the official ScaFi repository.

- Prepare your environment.

- Clone your own fork.

$ git clone git@github.com:<username>/scafi.git $ cd scafi $ git checkout -b develop origin/develop - Open your project with your favourite IDE, e.g., IntelliJ Idea Community Edition (note: it needs the Scala plugin installed)

- Open as sbt project

- Clone your own fork.

- Determine what your contribution will focus on. For instance, look at open issues.

- Develop.

- As we use (a variant of) git flow, use

feature-xxxbranches. - We strive to adopt development best practices. So, for instance, we leverage conventional commits: see predefined configuration.

- As we use (a variant of) git flow, use

- Merge your contribution.

- From your fork, open a pull request (PR)

- Wait for the project maintainers to perform a series of checks and merge your branch into the official repository.

- Congratulations! Go back to step 3.

Building the project

Once you have cloned your ScaFi repository, you can build the project using sbt.

You can run tests:

sbt +test

Generate the docs:

sbt unidoc

Something missing?

- If what is missing is of general interest, please open an Issue in the scafi.github.io repository.

- Otherwise, contact us!